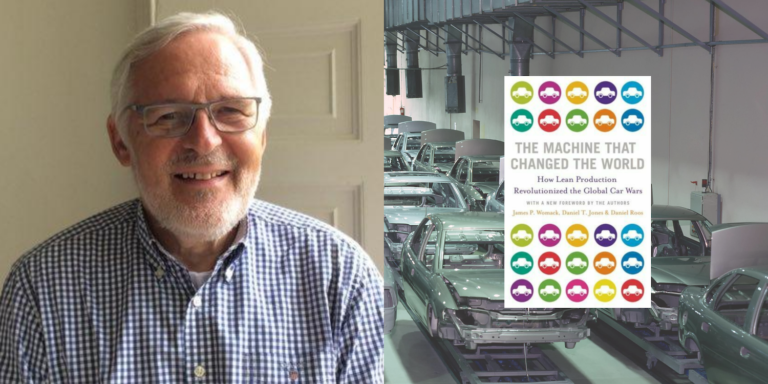

INTERVIEW – In the fall of 1990, a book was published that would kickstart a revolution in business. This week we are catching up with the authors to understand where we are and where we are headed. First up, Daniel Jones.

Interviewee: Daniel T Jones, Co-founder of the Lean Movement

Interviewer: Roberto Priolo, Managing Editor, Planet Lean

Roberto Priolo: People tend to think that The Machine that Changed the World is a book only about manufacturing, when really what you did in it was describing a whole system. In hindsight, is there something that you missed, that you did not see? And what did you get right?

Dan Jones: The robustness of our analysis and of the methodology, particularly on the production side, were absolutely sound. Nobody has been able to successfully challenge us on that. The book changed the way people understood competitiveness in the automotive industry. Our predictions of the fall of British Leyland and, more importantly, the fall into bankruptcy or near bankruptcy of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler were also accurate. So, I’d say we got the facts and the predictions right.

It’s true that we described a complete business system – even though we talked about “lean production”, to contrast it with the well-known concept of “mass production” – but people didn’t pick up on that because, at the time, we couldn’t tell them how to effectively achieve those outcomes. For that, we had to wait until Lean Thinking. Yet, there is no doubt Machine had a profound effect, leading to the creation of a movement. I can see why it’s still a classic.

RP: Part of that business system you described is product development. Today, LPPD has gained much attention, but it’s taken a long time. Why is that?

DJ: It’s important to remember that up until 1991, around the time the book came out, Toyota was still in catch-up mode after a disastrous start in the United States. Although the company had a faster development cycle, we didn’t completely see that that was what enabled Toyota to close the quality gap in performance – and even gain a competitive advantage. The full significance of lean applied to product development didn’t become clear until Toyota started experimenting with changing the technology – and that was after Machine came out. It was through the faster iteration of trying hybrids and electric that their product development system really came into its own. In retrospect, we have understood that the true significance of a faster product development cycle is about scaling up the appropriate technology faster than competitors.

Another important thing to note is that at the time the product development and engineering community were tiny compared with today. We didn’t have an active market, nor did we have access to the ex-Toyota folks who could really help us understand lean product development in detail. I’d say that the fact that product development didn’t receive much attention to start with was a function of history.

RP: What are the elements of Lean Thinking we’re still struggling to see truly accepted and understood in the community?

DJ: Lean has been a journey of discovery. Over the years we have uncovered deeper and deeper meanings and significance. I’ve argued that over time there’ve been six main changes in our thinking, in our paradigm. I call them “revolutions”:

- The first revolution stemmed from the realization that all work is the result of a set of activities or system of activities and that the value chain can only work if every step is performed right first time, on time. In a sense, that was the “quality revolution”.

- The second revolution is the understanding that the logistics of work are driven by customers – the “just-in-time” revolution.

- The third revolution is the introduction of the idea of continuous improvement, the methodology behind it – it was our “Kaizen revolution” and it had to do with the role of the line management, particularly in training.

- The fourth revolution concerned leadership and how leaders can build an infrastructure that supports learning and capability development across the organization.

- The fifth revolution was actually thinking back from the customer, and that’s where product development comes in.

- And the sixth revolution talks about how decisions are made and how strategy is incorporated and implemented, how leaders learn to focus on the right things and to relate high-level strategy to detailed execution on the ground or in engineering teams.

At each of those stages, we had to learn and discover new things. There was no theory we could look at. It’s been quite the journey, during which we’ve made a lot of mistakes and learned a lot of things. And I can’t help but think that journey’s not complete yet.

RP: In Machine, you discussed what you foresaw as the main obstacles preventing lean production from really taking root. Are you still happy with those?

DJ: I think these hindrances have become clearer. I see two major ones that stopped lean from automatically becoming the next management system.

The first is that the shareholder-first business model dominates the market: it’s easier for senior managers to put a bit more of a marketing effort in, control the market and make profits that way than deal with the difficulty of sorting out how their operations work. Traditional management is always going to look for the easiest thing to do, but the robustness of the American business model epitomised by GE is now creaking terribly. Having created lots of profits for a very few people, it’s just unsustainable going forward. It is no longer fit for purpose.

The second major obstacle was the false promise of the digital revolution, the idea that digital would replace human decision-making and leverage automation to better control activities, and that this would lead to higher profitability. That has actually shown not to be the case: technology has certainly allowed us to do things that we couldn’t do before, but it absolutely hasn’t saved any money in doing the existing things any better. In fact, it has added layers of cost and rigidities.

RP: Machine was more than just a book. It created a movement. What are your thoughts about how it spread?

DJ: It’s been an extraordinary journey, and I would not have envisaged that we would have created a global movement. I would not have believed that we would have reached, particularly, the practitioner world in the way we did.

Lean Thinking has spread wide, but how deep is still the key question. Looking back, I think we had a dilemma: as missionaries, we were trying to sell these ideas to a business community that was only interested in the efficiency bit. They wanted to know how they could just “add” lean to what they were doing to take waste of their system.

I think we succeeded at getting people to experiment with those ideas and see their power, but in hindsight I don’t think we were tough enough with the managers who were not willing to commit themselves to a lean transformation. We now realize that the transformations that work are the ones in which senior management recognizes that lean is a different business model and successfully leads the change themselves by energizing the shop floor. So, I think we should have done what the Japanese sensei we observed were doing.

RP: Interesting. What are the limits of traditional consulting in your opinion?

DJ: There was always a debate about the sensei versus the consulting path in the lean movement. I was always on the sensei side and got a lot of stick for it because companies were really in love with traditional consulting. That’s where they felt most comfortable, because they thought they could just invite senior experts in to carpet train people or design a new IT system that would magically solve all business problems.

One of the most important lessons we have learned in our movement, however, is that you can’t “do lean” to people, that you can’t design systems and force people to work in them. The only things we learn are the ones we learn to do yourself, which is why teaching, coaching and mentoring have so much relevance in our world. Yet, those words are problematic because they have mental baggage associated with the old definition of consulting.

Effectively teaching lean doesn’t mean to coach, mentor or train. The sensei is somebody who’s been there before, who can guide you by asking the right questions and encouraging to think differently about problems.

I’m critical of traditional consulting, but not about those who are consulting to help people learn to do it themselves. In fact, one regret I have is that we didn’t focus enough on creating a structured development process for training sensei. Luckily, I think people are starting to understand how important this is more and more: recent books like The Lean Sensei or Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn are changing the rhetoric, and I have no doubt they will help us to develop more sensei.

RP: What elements of lean leadership as we know it today were you able to observe during your research for Machine? And how did that understanding evolve?

DJ: Something we observed right from the start was how tough the Toyota sensei were on the managers (although part of it was theatrics). They were guiding the learning of the leaders, showing them how to connect the detailed improvement they were making on the shop floor with the business results and the development of people’s capabilities. We could have learned more from them.

Another thing that has been important in our understanding of leadership was observing how leaders built a learning support network across the company, by deploying A3 Thinking for example.

Today, we understand a lot more about these and other elements of lean leadership. Some of these learnings were crystallized in The Lean Strategy, where my co-authors and I talk about the 4F Framework. I think that’s extremely important in understanding how strategy is formulated, how decisions are made, how the dialogue happens in the hoshin process to support the implementation of those decisions, and the encouragement and the focusing of proposals from below in the organization to close the identified gaps.

RP: One final question. The world has changed beyond recognition in the past three decades. Why do you think that the message that Machine brings, and therefore Lean Thinking, is still so relevant?

DJ: Recent events – like the Black Lives Matter movement and the tearing down of Colston statue in Bristol – have shone a light on the fact that the Anglo-Saxon business model was built upon the exploitation of people, markets, and materials. (More on this in another article soon.)

Lean is an alternative to this. It’s a model based on respect for people, that makes for a responsible use of resources, one that is actually resilient. That sounds to me as being very much in tune with our times. I think it’s possible to reconfigure or re-describe the lean business model as an alternative to traditional capitalism that resonates with people and that addresses the challenges our society faces.

We are witnessing a shift in the tectonic plates of geopolitics, with the rise of China and the eclipse of the United States. Climate change is clearly with us and we can’t escape having to deal with it. And, of course, there is now the Covid-19 pandemic, which is transforming how we think about health and we relate to each other. A lean business model has answers for all of these challenges, answers that are rooted in scientific thinking – at a time when more and more people, especially those left behind by the inequality we have ignored for so long, are rejecting science in favor of the false promises made by the populists.

I believe that the lasting legacy of Lean Thinking is the democratization of the experience of using the scientific method in our daily lives, something I see as a powerful counterweight to emotions, fake news, bigotry.