FEATURE – In this personal account, the author explains how Lean Thinking inspires her painting process, debunking the myth that the methodology stifles creativity.

I smile whenever someone comes to me and says, “Lean is not for me. I am not into that amount of detail.”

Those who consider themselves “big-picture people” and “creative” typically tend to think of lean as a tedious undertaking and believe that detail will end up killing their ideas. (It’s the old misconception that lean stifles creativity.) What I have come to realize, however, is that they might think of themselves as big-picture people but actually do not know a great deal about how big pictures are created. The truth is, the bigger the picture. The more detailed thinking will be required.

I don’t consider myself a great artist, but every now and then, I am motivated to paint a picture. In my experience, turning out a visually pleasing picture is not the free-spirited action people may think it is; painting a picture is full of rules and processes, problems to solve, and decisions to make.

These rules and processes were designed and used by the great artists of the ages. They have never prevented the creative process, only aligned the work to the vision.

In my process as an artist, it is natural to use Lean Thinking to guide me.

The first step for me is to draw the painting’s house – yes, like the lean house.

- What’s in the roof? What do I need to align my work to? The top of my house (my goal) is a picture that is pleasing to look at that expresses my emotion. An image that provokes thought and emotion in others.

- The foundation of the house is the current skills that I have.

- The left pillar is the rules and tools used to develop my skills while I paint the picture.

- The right pillar is the practice, the sketches, and the actual work of painting the picture.

- The center of the house is my own willingness to learn, experiment, and critique the work I am doing to allow my skills to grow. This behavior includes my willingness to stand back and look at the picture to improve my understanding.

Now that we understand the house let us look at the process.

1. Decide what to paint;

2. Source the canvas to be used;

3. Set up the easel and fit the canvas onto it;

4. Decide upon the media that will be used;

5. Decide what tools are needed;

6. Decide on the cleaning fluid required;

7. Gather all these requirements next to the easel.

When all these items are together, I plan the painting itself by asking myself a few questions.

How am I going to lay out this painting? What color and tones will I use to express the feel of the artwork? What initial shapes will I sketch? What will I do with the empty space to create balance? Am I using the golden ratio? How do I ensure perspectives and proportions are correct? How will I give it life?

After painting the picture, I leave it in view for a couple of days. This little bit of time allows me to see areas that need improvement – more light in one place, more shadow in another, a mouth that’s too wide or a nose that’s too pronounced.

By asking all these questions and using learned techniques, I problem-solve my way through the painting, paying attention to the details and continuously checking the work by standing back and observing the outcome.

Does this not sound a lot like PDCA? Does the waiting and observation period not sound a little like kaizen?

Yes, each painting is different – or should I say situational? In reality, if I had not used the processes, the result would not have aligned with my vision.

What I have also found is that the bigger the painting, the more difficult it is to plan, because the proportions and perspective become challenging. When a team of artists works on a mural, conforming to unity must be considered as the different styles need to be taken into account.

So, the more significant the picture, the more the visionary needs to understand the detail and techniques to keep alignment to the vision. Let us think about the building of a bridge. The bridge has a plan, but many different materials are used, and diverse skills are required. The project manager is the one who understands the big picture, but he also understands the timing and detail of each process. This way, he or she keeps the entire team in alignment to plan.

When self-proclaimed no-detail, big-picture people come to me, I might smile, but, in my heart, I know that they either do not understand the work or don’t want to do it. I usually start the transformation process hoping that the former is the case, that they don’t understand the work, because this is something that Lean Thinking and its tools can fix by revealing just how vital the work is. When the people involved don’t want to do the work, we face an entirely different challenge, and things often don’t end well.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some people only see detail and struggle to step back from the painting and observe the big picture. These personality types are easier to align with the vision. If one assists them and teaches them how to see, they will be ready to do the work and often become the most successful disciples of Lean thinking.

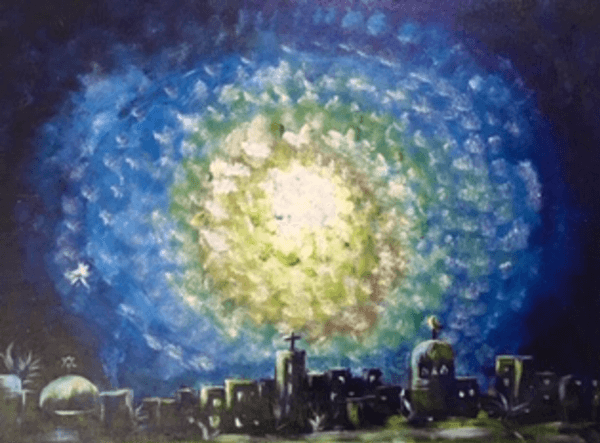

By the way, the paintings in this article are mine. The first one I painted after the September 11th, 2001 attacks in the United States, a time that showed both the worst and the best of men. The second one, much more recent, represents Lady Wisdom, who is increasingly being ignored during the Covid-19 pandemic. She shouts of the streets, asking the children of men to listen to her voice.