Open most lean books and you get a feeling that Kanban is an afterthought – one of the many “tools” that we’re supposed to move away from. I plead guilty, I’ve written as much. But, let’s face it, there can be no Lean Thinking without Kanban.

Lean is unique as a management approach because it doesn’t aim to tell people what to think or what to do (Taylorism), but how to think about things so they come up with their own ideas, insights and initiatives. This is what makes lean both so appealing (in fact, fun!) and disquieting for many bosses who prefer to prove they’re in charge (think as I do, do as I say) rather than improve tings (how do you see the problem? What would you do?).

But thinking never happens in a vacuum. We think in context and, more so, we think in visual context. Because visual cues go straight to our brains, we are less aware of them than what we’re told. Being told something is harder to process, as it goes through language, argument, discussion and so on, means we retain very little of it. On the other hand, seeing is believing, literally. If someone shows you something obviously wrong, your brain first believes it and then you have to work at disbelieving it.

If you want people to be smart about what they do, first you’ve got to design a smart environment for them to think in. All work environments are engineered – if sometimes accidentally. The work environment asks the questions, although we’re rarely aware of it. This fundamental insight is why so many lean techniques center on defining the work environment itself before jumping in on the problem: andon, kanban, 5S, 4M, etc.

Back in the 1950s, Toyota engineers figured out that the key to quality and productivity was lead-time, not unit cost. If you focus on unit cost, you end up producing volumes you can’t sell, which you have to move around, store, re-check and eventually throw away. If you focus on lead-time, you increase rotation of your capital use, can’t allow for mistakes (you can’t just discard a faulty part and take the next one if you only have five parts in a box), avoid exceptional costs and become vastly more productive all around. And the trick to visualizing lead-time is Kanban.

Any product is made to order. The box of cereal on the supermarket shelf is made in batches, but what the customer really takes away from the store is a basket of products – which is a made-to-order assembly of purchases wrapped in a bag. Imagine you want to fix yourself lunch. You can completely assemble it to order, by going to the shop, picking the ingredients for a salad, returning home, making it and eating it – there is a clear lead-time here from when you leave your place to go to the supermarket to when you are eating your salad.

Or, you can open the fridge, find a ready-made dish, stick it in the micro-wave and eat it. Lead-time is much shorter, but you need to have the dish already purchased in the icebox.

Or you can open the cupboard, open one of the many packs of pasta you have stored there, think that you must stop buying all that pasta if you’re not going to eat it, and then cook it.

Yes, you can make everything completely to order, including thinking up the recipe for the salad as you feel it, but in fact sooner or later you will hit two barriers:

- The stock barrier: some items need to be held in stock – it wouldn’t make any sense to purchase olive oil by the spoonful.

- The batch barrier: some items are purchased in batches because we don’t go to the supermarket every day and that is where they’re held.

The trick to Kanban is to stick a stock replenishment card at each point where you hit the stock barrier, as opposed to batch it. When you take a ready-made dish from the icebox, you know you’ve got to purchase one. When you take a beer from the fridge, you know you’ve got to put one back to chill.

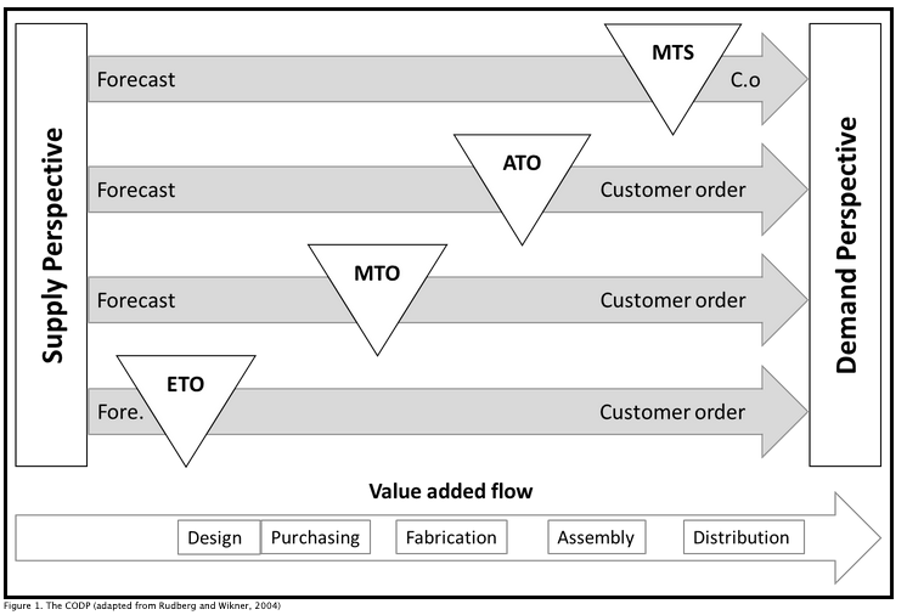

Technically, this is called the customer order decoupling point (CODP). It can be used to distinguish between different manufacturing approaches, such as engineer-to-order (ETO), make-to-order (MTO), assemble-to-order (ATO), and make-to-stock (MTS). As illustrated below, the CODP separates the part of the supply chain that responds directly to customer demand from the part that relies on forecasts and speculation.

Whatever the activity, you can look at its lead-time, trace the time line back to the stock point – when you need ingredients off the shelf – and then, rather than batch their production with a production instruction (I always buy four packets of pasta when I go to the supermarket), use a stock replenishment Kanban (use one, buy one). This Kanban will immediately reveal something in a visual way:

- Your real consumption pattern: aha! You don’t eat that much pasta after all, which is why you keep having all these packs accumulate. But then you often fall short of olives.

- All the mishaps in your supply system: the missing product on the supermarket shelf, the queue at the till, the past date dish in your fridge, etc.

- And focus on quality: you realize you really don’t like lasagna, but you keep buying some and not eating it because you’ve got chicken tikka on stock as well. Stop buying lasagna rather than throw it away.

All these kinks now appear very visually – you hit all the problems in your lunch value stream. As you solve them one by one, the workflow progressively becomes smooth and seamless and the overall cost of lunch goes down as enjoyment goes up.

“Sell one, make one” seems simple enough, but it’s a real revolution in how to design a work environment. It changes how people think about scheduling their work and doing the work itself because it changes the concrete problems they hit upon and have to sort out. “Sell one, make one”, visualized by Kanban, is the entry point to Lean Thinking. You can have the best intentions in the world about coaching people and asking them to take responsibility and leadership for developing themselves and others, but without “sell one, make one”, you’re simply solving the wrong problems.

Yes, lean is all about kaizen: self-study of work to improve and gain deeper insights into what we do. But kaizen starts with Kanban. Without Kanban, we don’t know what to improve, because we can’t visualize the lead-time, and the waste of time – time is the only resource we will never have more of. Start with Kanban.