Vision is such a potent sense that we tend to recall pictures much better than we do written or spoken words. Lean practitioners know the power of visual thinking well. For example, remember Kaoru Ishikawa’s seven basic tools of quality – Pareto chart, cause and effect diagram, stratification, check sheet, histogram, scatter diagram, and graph and control chart? Only one is non-visual (stratification). These simple, but powerful tools have stood the test of time, and are still useful today.

In this article, I want to talk about three practical applications of visual thinking that aim respectively at:

- rapidly testing our assumption and preconceptions;

- asking deeper and more pertinent questions;

- distributing knowledge that needs to be regularly used.

USING VISUALS TO TEST ASSUMPTIONS

Let’s imagine a sales team in a software company that is looking to increase the revenue they generate. They have a digital product, which is primarily sold through the website. A fair assumption for them to make would be to think that if they can bring more traffic to their sales page, the revenue numbers will go up.

Rather than jumping to a solution and spending money on advertising to bring more traffic to the website, the team decides to look at the numbers. They go into their web analytics dashboard and download data on the number of sessions and visits per month. They also download their sales data, organized by month and by product.

The first question they ask themselves is: “Is there a correlation between the number of website sessions and sales?”

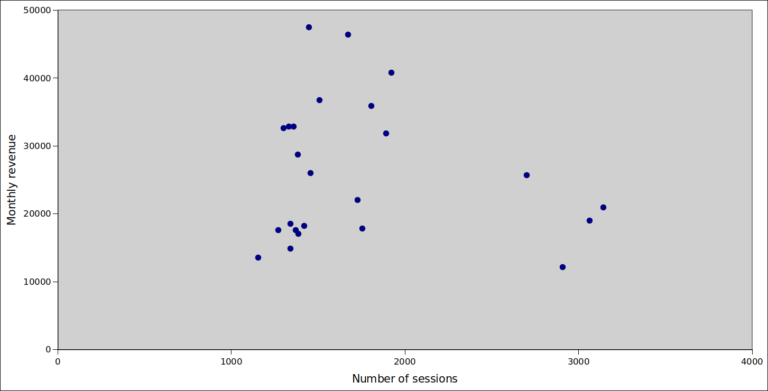

Here is what the data says:

What do you see here? What would you answer? How would you proceed?

First, the team notices that there seems to be no correlation between number of sessions and monthly revenue. Secondly, they become curious about outliers: three dots on the top representing the highest revenue and three dots on the right representing the highest number of sessions. Finally, they start asking themselves how they can better understand the quality of their sessions.

By visualizing data, the team is able to rapidly test their initial assumption. They used a mix of quantitative and qualitative data to understand what was happening, why and how. In the end, they successfully improve their monthly revenue.

USING VISUALS TO ASK BETTER QUESTIONS

Imagine you have a brilliant idea that you want to refine. You could try to write it down, perhaps using a template, like a business plan or a suggestion card. If these templates are any good, you should be able to use them as a checklist of the items you need to address. You would go item by item, thinking each one through, writing down your answers, then refining them further until you are satisfied. Or least that’s how it should go.

In most cases, however, we end up spending too much time on these tools, with very little to show for. Too often, the essence of the idea gets lost somewhere in these documents, frequently together with the narrative and the story of how the idea came to be (which are critical for sharing it with others). This is exactly why A3 problem solving is so useful: it provides a structure that allows you to retain the narrative around the problem and its proposed solution and it forces you to ask all the difficult questions.

What if you were to try to use such a visual tool to describe your idea?

The good news is that there are a lot of them out there that you can choose from. The bad news is that… there are a lot of them out there that you can choose from! When selecting one, you should consider the tool’s clarity of instructions (do you understand how to use it?), usability (does it get in our way or make things easier?), and internal logic (does it support narrative explanation or is it all over the place?).

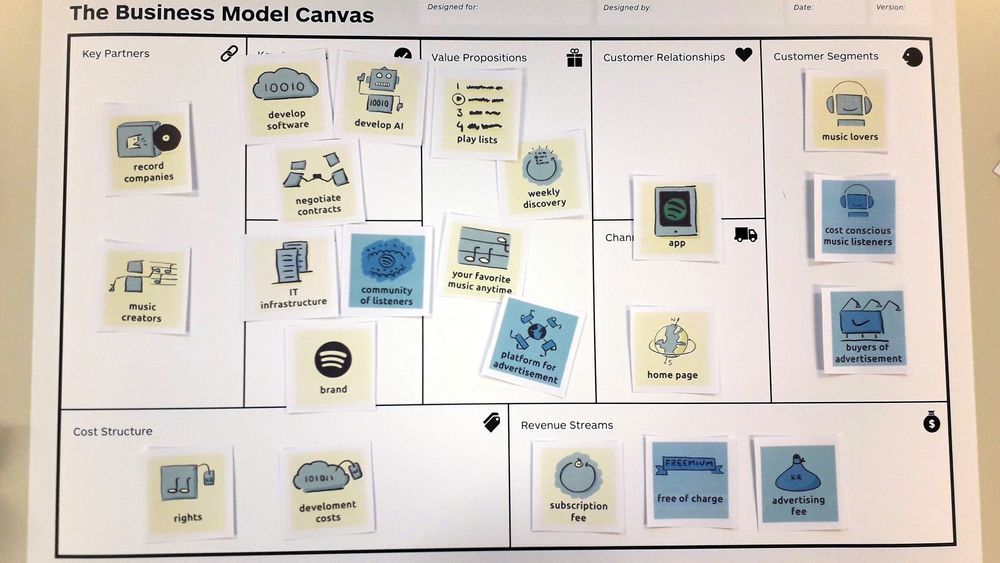

Take a look at the photo below, referring to a music-sharing website. (The Business Model Canvas was developed by Alexander Osterwalder, whereas the block illustrations are by Lauris Muzikants.) What is it telling you? What stories do you see? What would you ask next?

Notice how on the right side we have a clear view of who the customers are and what value is provided to them. There is color-coding to differentiate customer groups: music lovers with a paid account, music lovers with a free account, and advertisers. We have a clear understanding of what each of these three groups bring back to the organization: a subscription fee from paying subscribers and advertisement fee from the advertisers. Only free users get exposed to ads.

Looking to the left, we can see key elements of the operating model, namely the activities, resources and partners required to deliver the value to customers. We can see that this idea is based on providing music, but without actually owning it. That means the company must partner with record labels and musicians. They focus on developing top-notch software and infrastructure, which they are keeping in-house. Finally, looking at the bottom row, we can see what the key drivers of cost and revenue are.

Let’s stop here for a moment and observe what just happened. With a single illustration and just a few words we were able to explain and convey an idea that would have otherwise taken pages and pages of text.

To continue with the example, the question I posed last is what we could ask next. A barrage of questions, really, depending on the direction in which we want to head. If you are happy with the idea on the canvas, you could ask what must happen to allow this idea to work as described. If you want to increase the scope, you could ask how the idea would change if you added podcast lovers as one of the segments.

The operating model is always a great place to ask provocative question. Some example for this case would be what would happen if you removed the IT infrastructure or what would happen if you made music yourself. If you are stuck, you can always go for one of my favorite questions – How does this make sense?

By visualizing the idea, we have created an artefact – object – that we can further discuss, analyze and test. It’s much easier, more respectful and less hurtful to discuss a piece of paper than to go at each other.

USING VISUALS TO DISTRIBUTE KNOWLEDGE EFFICIENTLY

The first two applications I described are about enhancing our learning and deepening our understanding by using visual methods. Now I want to draw your attention to an opportunity to unlock even more value from visual thinking without “discarding knowledge” – something Ward and Sobek warn us against in Lean Product and Process Development.

In their recently-published White Paper on reusing knowledge, José Ferro and Fernando Rodrigues echo this idea when they write: “Today’s highly competitive market requires companies to engage in ever faster technology development while maintaining costs under control, in order to cope with increased pressure from ever more elaborate customer demands. Reusing knowledge is one of the most useful approaches to shorten time-to-market cycles, to reduce risks and costs, and to increase the chances of success.”

It is with this in mind that Ward and Sobek also advise us to make knowledge capture a priority and to train people and create systems that allow us to transform data into useful knowledge. Trade-off curves are a great example of visualization that pack a lot of knowledge into a small space, so the information can be quickly digested and interpreted.

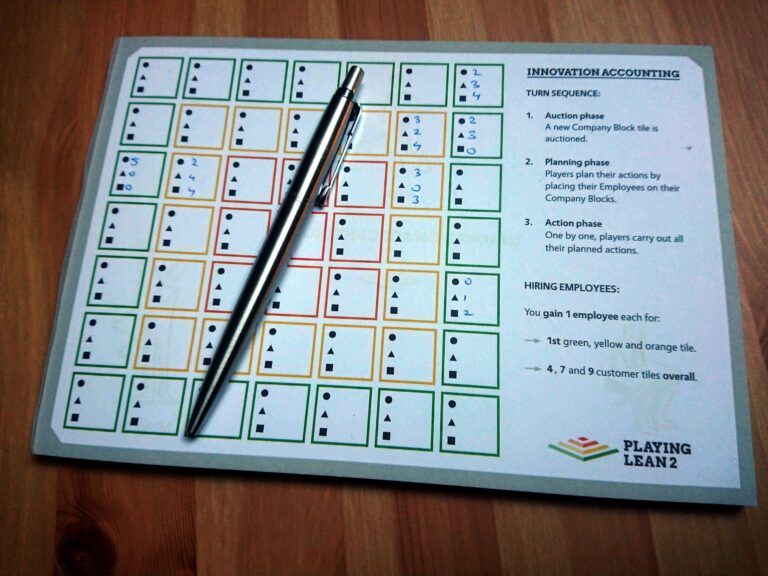

Another concept discussed in the book is that of a knowledge brief, a single sheet on which all information relevant to the matter at hand is recorded. Playing Lean, a board game that supports innovation and entrepreneurship, deliberately includes simple visualizations to make said concepts tangible.

For example, to make knowledge capture easy and reusable, each team playing the game is given an Innovation Accounting Sheet. It consists of a grid that mimics the market and customers, with blank fields in which teams can write the results of their experiment (for instance, what the customer wants). As teams run experiments, they populate the innovation accounting sheet, which then serves as a visual overview of what they know, which in turn enables them to take informed decisions.

In conclusion, written reports still have their role to play in documenting our learning, but if we want to create knowledge that can be used on a daily basis we truly need to consider visualizing it. Engaging with trade-off curves, A3 storyboards, knowledge briefs, canvases, and other visual tools is less cognitively demanding, leaving us more brain power to ask the right questions.